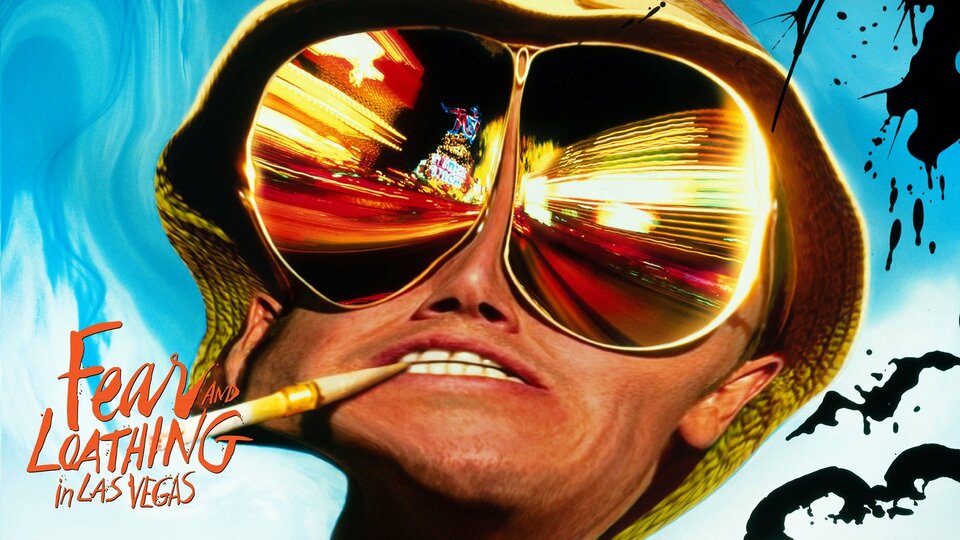

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), directed by Terry Gilliam, is a darkly comic and surreal journey through the countercultural underbelly of America. Based on Hunter S. Thompson's novel, the film stars Johnny Depp as Raoul Duke, a paranoid, drug-addled journalist, and Benicio del Toro as his attorney, Dr. Gonzo. Together, they embark on a chaotic road trip to Las Vegas to cover a story about the American Dream—but instead, they spiral deeper into a psychedelic maelstrom of excess and self-destruction.

The film is a visual and thematic rollercoaster, using bold and disorienting cinematography to immerse the audience in the frenetic minds of its protagonists. It delves into themes of disillusionment, existential crisis, and the collapse of the 1960s counterculture. The film explores the absurdity of the American Dream, showing how Duke and Gonzo’s journey is less about finding meaning and more about losing themselves in a haze of drugs, hallucinations, and madness.

Despite the film’s apparent madness, it is also a sharp commentary on the disillusionment of the time. Thompson's original text, and Gilliam's interpretation, highlights the absurdity of pursuing the "American Dream" in a society that has lost its sense of purpose. The film’s vivid imagery, bizarre characters, and rapid-fire dialogue reflect the anarchic spirit of the era. Depp’s portrayal of Duke captures the essence of Thompson’s gonzo journalism—wild, self-indulgent, and profoundly out of touch with reality. Del Toro, as Dr. Gonzo, brings a manic energy that perfectly complements Depp’s more subdued yet increasingly paranoid performance.

The film’s disorienting narrative style may alienate some viewers, but it effectively mirrors the mental state of its protagonists. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is a brilliant, albeit exhausting, meditation on the folly of chasing an ideal that, when pursued recklessly, ultimately leads to destruction.

If Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas were to receive a continuation or a spiritual sequel, it could explore the aftermath of the chaotic journey through Las Vegas. Imagine Raoul Duke and Dr. Gonzo emerging from their trip, battered and broken, but still haunted by the ghosts of their previous escapades. The sequel could explore their attempts to navigate the wreckage of their past decisions—perhaps they find themselves in a society even more fractured and nihilistic than the one they left behind in the original film.

The sequel could introduce new characters who represent the lost generations after the 1960s idealism has faded. Duke, now older and perhaps a little wiser (though still unreliable), may find himself grappling with the consequences of his actions and the erosion of the values he once championed. A new Las Vegas, now dominated by corporate greed and digital distraction, could serve as the backdrop for a journey into a new kind of madness, where the line between reality and illusion is even blurrier.

Visually, it would continue Gilliam’s tradition of bold, often surreal imagery, using modern technology to push the envelope on what was possible in the first film. The sequel could juxtapose the ghosts of the past with a disorienting vision of the future, questioning whether the pursuit of happiness, freedom, or even meaning is just as elusive now as it was in the 1960s.

In this speculative continuation, the film might reflect how the American Dream continues to be sold, consumed, and shattered—much like the characters who once chased it.